By Constance Arthur

There has been a lot of conversation around reparations for families of former slaves. Some churches have looked at their histories and found the presence of slavery in their church, not just in the history of family members attending the church. There have been stories of churches in the North finding unmarked graves on their property containing the remains of African Americans. There are stories of church members selling a few of their slaves to purchase things the church needed to maintain its structure. There is the history of Salem, North Carolina and how that community has suffered from displacement, redlining and home condemnation. The association with the Moravian Church did not raise them out of poverty or deliver the community out of racism. Some congregations with these discoveries have looked for ways to reconcile these past injustices. Some have responded with statements with apologetic tones. Others have no idea how to reconcile. So, what would reparations look like for the church?

Most think let’s find a way to throw money at it. Who do you write a check to? In some instances the families may be known, in most it is not clear. Those who lost land (my family) may have paperwork that can be traced to the property. Who owns it now? Is the land producing revenue for them? Perhaps we could end the practice of condemning the homes of Black people when their community is sitting where they want to build a new subdivision, golf course or highway. Most of the time, when homeowners are reimbursed they don’t get enough money for their land and homes to purchase a new home in the subdivision. Members of the community do not get enough money to move out and move up. They usually end up renting and losing home ownership status. This occurred down the road from my house in Roseville, North Carolina. The majority of that community is now renting in Louisburg, North Carolina. With the expansion of Route 401, there will be more displacement. Reparations involving money can take place if fair and equitable practices are carried out for those who have property.

One landowner here in Georgia told me the story of his family. His son does not want to farm but would like to find another way to capitalize on the work of his father and other relatives. His son thought renting or leasing some of the land to an electric company for a solar collector farm would be a sustainable way to go. The land would be income producing and benefiting the residents of the county. The deal was a go since most of it was conducted over the phone and computer. An appointment was set up for the company to come by the house and have some papers signed. Once they saw who they were dealing with, the deal went sour. They reneged on having the contract signed.

United Negro College Fund

I suggest educational opportunities. Give financial support to the United Negro College Fund and support schools with professors and endowments. Black communities in our cities and in the South have been kept from becoming competitive in the workforce. Around here, that has been done by not allocating enough tax dollars to predominantly Black public schools. During COVID, most children did not have computer equipment or expertise for studying at home. Some went to McDonalds to get an Internet connection. I’ve known some boys who were blackballed by their football coach which prevented them from getting scholarships to college. With a steady income, a family can put money back into the community. One philanthropist who understands this is MacKenzie Scott, (Jeff Bezos ex-wife). She surprised the Historically Black College and University (HBCU) community with her donation of $560 million to 23 HBCUs—public and private. We can hold the U.S. Department of Education—as the agency of the federal government that establishes policy and administers and coordinates most federal assistance to education—accountable. They can do more. The Department of Education can make sure there is money going to these schools and communities where the school boards are managed by people who live outside of these depraved communities. COVID has revealed the weakened infrastructure of public school systems. Bottom line, strategies to move tax dollars out of Black neighborhoods has been working for many years beginning with civil rights to integrate schools. Gentrifying neighborhoods is another strategy that has been working for years to dismantle these communities. In these instances reparations would be to work towards financially supporting these communities. Being active on school boards and city councils is a way to utilize power and counter the actions and plans of those determined to limit minority participation in our work force and other social institutions.

Classroom curriculum has already been designed by the Department of Education to include the experience of African Americans, Hispanics and Native Americans. This was done before our history was categorized in a way that alienates people from it—before Critical Race Theory which is not understood or connected to education correctly. We can teach the truth. Telling the truth means, here is what we did. Here is what we are doing now. Children and adults alike need to know and understand harm so we can strive for equality and fairness. Harm is a part of our past and our present. Children need the tools to overcome harm and injustice for a better future.

For me, reparations looks like open, real, and true education for everyone. With education, people can develop a philosophy of life that reflects the idea, “we are all created in the image of God.” There are universal truths that weave throughout our major religions. Focusing on what we have in common across the globe can be the basis for an ethical philosophy we can all hold onto and practice. I believe most people in our country want to live together as the United States of America, a democratic nation, giving no one group the upper hand to control or hold down any other group. Those who want to live together are already practicing an ethical lifestyle to some extent. Our ethics and values are what will inform our behavior towards a future where we can all “LIVE LONG AND PROSPER.”

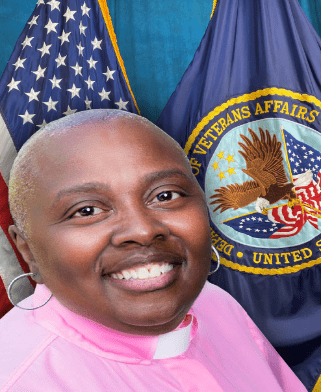

Chaplain Constance G. Arthur, MDiv, BCC, earned degrees from Temple University and Boston University School of Theology, and studied with Harvard Divinity School’s Executive Education Program, “Religious Resources for Living Through Crisis”, 2020 and 2021. She is a Board Certified Chaplain at the Veterans Administration Medical Center in Dublin, Georgia, where she has established the Chaplain Service Mental Health Outpatient Clinic which provides pastoral care and counseling to Veterans with PTSD and Moral Injury. She is an Alliance-endorsed chaplain and serves on the CAIRN leadership team.

Recent Comments