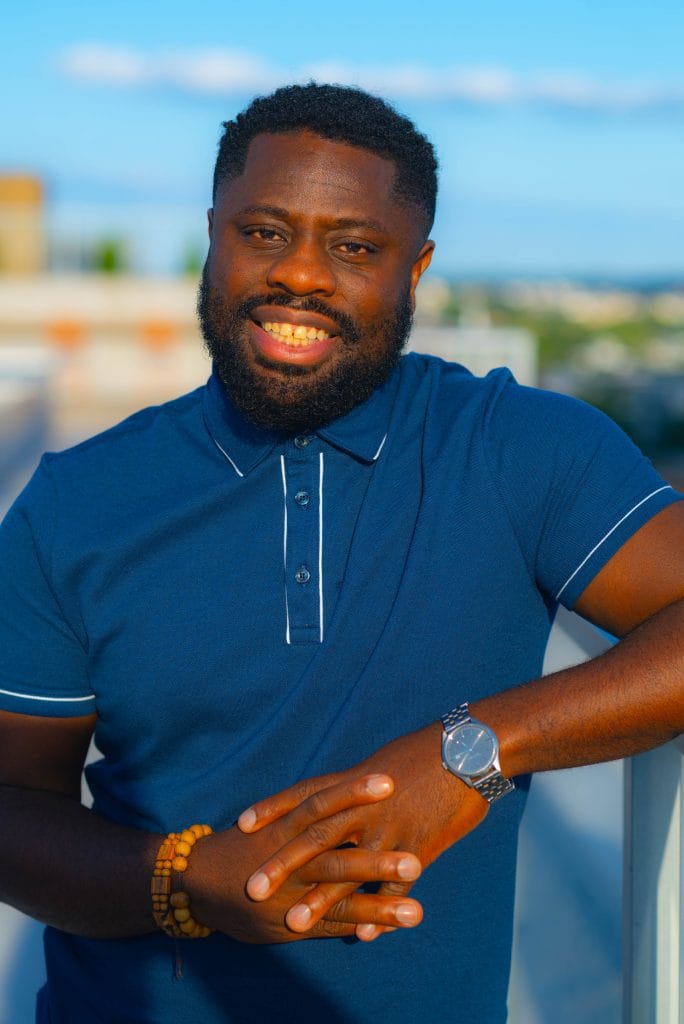

by Reverend Elijah Zehyoue, Ph.D.

On Saturday morning October 7th, we were awakened to the news that Hamas had carried out one of the deadliest attacks on Israel in recent history. Like many others around the world, I joined my denomination and other ecumenical and interfaith partners and other people of conscience in condemning that attack and the antisemitism and Islamophobia that emerged even in those early moments. My denomination and our partners at the Churches for Middle East Peace (CMEP) continue to demand a release of all the hostages. And like many others, I continue to deepen my knowledge as I try to understand why this happened.

If I’m honest, for the first two weeks I was lost in the fog and could not figure out which way to go. I knew that my friends who had been supporting the Palestine cause for many decades were right that the attack had to be understood in the larger context and nearly 75-year history of the Israeli occupation, blockade, apartheid, and violence. And although I have never been to the region, every Black person I have trusted on every other major social, political, historical, and ethical issue—from Michelle Alexander, to Cornel West, to Angela Davis, and Ta-nahesi Coates and so many more—have all communicated that based upon their experiences Palestinians were treated similarly, if not worse, than African Americans and that segregation and dispossession is a daily part of Palestinian life. At the same time, I also have deep compassion for the fear coming from the Jewish community and my friends and colleagues with close ties to Israel, who like me have tried to be a voice of dissent against the injustice of the government and support the Palestinian people. I know that the visceral experience of violence is always scary. This dilemma made it difficult to know how to raise my moral voice in this significant moment. And in some ways that difficulty has not subsided. For there is new information coming out every day, and because we are dealing with people, their histories, and a number of competing political narratives, real and imagined, this situation is inherently complex. But no situation of human crisis is ever not complex, in part because they happen in the realm of human relations and power which often have many overlapping and interwoven parts. But complexity doesn’t mean that moral clarity will not or cannot be found. It only means that we must rely on our most trusted resources to discern what is acceptable moral, good, and true and that should guide how we use our voice.

On April 4, 1967, Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. stood in the pulpit of the historic social justice Riverside Church in uptown New York City to make the case for why he was against the Vietnam war. King’s sermon was met with hostility, anger, and violence. Many civil rights leaders distanced themselves from him, and others criticized him because they thought civil rights antiracism had nothing to do with Vietnam. But King, as the leader of the global human rights movement for freedom, boldly spoke about how his whole career, from Dexter Avenue in Montgomery through the entire civil rights movement, had brought him to this point. At the core of King’s argument was that his position against the Vietnam War was because of his vocation as a Baptist minister and a proponent of nonviolence. In explaining this, he said the following:

As I have walked among the desperate, rejected and angry young men I have told them that Molotov cocktails and rifles would not solve their problems. I have tried to offer them my deepest compassion while maintaining my conviction that social change comes most meaningfully through nonviolent action. But they asked—and rightly so—what about Vietnam? They asked if our own nation wasn’t using massive doses of violence to solve its problems, to bring about the changes it wanted. Their questions hit home, and I knew that I could never again raise my voice against the violence of the oppressed in the ghettos without having first spoken clearly to the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today—my own government. For the sake of those boys, for the sake of this government, for the sake of hundreds of thousands trembling under our violence, I cannot be silent.

King’s words from five decades ago remain powerful and relevant today as Israel, with unrelenting support from the United States, unleashes a scourge of violence and collectively punishes the people of the Gaza Strip.

I believe that I have found my moral clarity today. What is happening in Gaza right now is simply not acceptable, it is morally unjustifiable, and it is wrong. It is humanitarian catastrophe of tremendous proportion; it is indiscriminate violence; it is collective punishment; it is revenge, and if it continues as it has with a death toll surpassing 10,000 people, half of them children, it is genocide. As a Baptist minister, historian, scholar, and a student of the nonviolent freedom tradition, I cannot stand by as it continues. I will not stand by as it continues. And in fact it is in this moment that I recommit myself to nonviolence and the moral clarity, theological profundity, and liberation inherent in its ideals.

Nonviolence is a theology and a strategy for conflict resolution—it is the idea that ultimately violence will not solve our problems. And while non violence recognizes that violence exists in the world and remains available as a tool used by both the oppressed and oppressors and is even an effective and legitimate tool at times, nonviolence seeks to use persuasion to move the world away from violence because of its deep awareness of the ultimate toll that violence takes on all who partake of it. It recognizes that violence simply begets violence. And this is precisely the predicament in Gaza today. The current justification for the siege of Gaza is violence. And violence is returned with more violence. Violence is the first solution, and last resort, while bearing few tangible results. This is why advocates of nonviolence urge all parties to seriously consider it as a part of a real long-term solution to this problem.

Advocates of nonviolence aren’t just talking the talk, they are walking the walk. All over the world, there have been nonviolent protests to demand that the most powerful governments, including the United States, use their power to stop the carnage in Gaza. Just last week an interfaith, multiracial, and pluralistic coalition of 300,000 people gathered in Washington, DC to petition their government for a redress of grievances. Hundreds of Jewish, Christian, Muslim, nonreligious, clergy, students, and activists have participated in civil disobedience to try to draw attention to the dire and urgent humanitarian situation in Gaza.

I believe that I have found my moral clarity today. What is happening in Gaza right now is simply not acceptable, it is morally unjustifiable, and it is wrong. It is humanitarian catastrophe of tremendous proportion; it is indiscriminate violence; it is collective punishment; it is revenge, and if it continues as it has with a death toll surpassing 10,000 people, half of them children, it is genocide. As a Baptist minister, historian, scholar, and a student of the nonviolent freedom tradition, I cannot stand by as it continues. I will not stand by as it continues. And in fact it is in this moment that I recommit myself to nonviolence and the moral clarity, theological profundity, and liberation inherent in its ideals.

At its core nonviolence recognizes the shared humanity in the world and appeals to the whole world to participate in it. But nonviolence doesn’t simply stop there. It also, in my view, has a power analysis and recognizes that when there is such an asymmetry of power, as in the case of Israel and Gaza, that the group with much greater power has a moral responsibility to work for the cessation of violence, especially when so many innocent people are caught in the mix. This is why Dr. King’s words quoted above were directed at the United States. As a citizen of the United States and someone who was working to make the ideals of the United States real, he believed, as I believe, that the values of our Christian faith mandate that we take human life seriously. This is why he did everything he did even though he lived in a country that scorned his values. His government, our government was in fact, and continues to be the greatest purveyor of violence in the world. This is not good for the world or the country. But King’s knowledge wasn’t just informed by Vietnam but also by Birmingham; it wasn’t informed by just Hanoi but also Mississippi; it did not come just from international politics but also from domestic politics. I know It is easy to think of nonviolence as weak and impractical, as something perhaps left to the pie in the sky folks who have no conception of realpolitik. I know it is easy to call nonviolence a distraction, or worse something that will actually enable further harm. I know It is easy to dismiss nonviolence as something that could work for the civil rights movement but not something that could ever be viable for Israel or the United States. I think what that misses is the level of violence civil rights leaders were actually up against. The thing that is often missed is that the theology and strategy of nonviolence practiced during the civil rights movement emerged in a very real situation of violence. Black folks lived in the midst of real terror, from the KKK to the White Citizens Council to the local police. Violence was a daily reality in the Jim Crow South and segregated North; it was common on the hills of Mississippi and on the mountains throughout the country. It was a fact of life. And yet, this fact of life is precisely why so many Black leaders chose to deal with their situation of violence with nonviolence—this didn’t make them weak, it made them strong.

Every year we are told to remember these Black leaders from the civil rights movement. Every year, I am asked to teach, or preach, or write about them. Every year we stop and pause to celebrate Dr. King, but towards what end? Is it to keep the ideals of those people who loved freedom frozen in a museum, or is it possible that those Black folks might actually have something to teach the country they lived in and the people who lead it. The current way we treat the ideals of the civil rights movements is that those ideals are for other people, for the weak and not the powerful. For those fighting for freedom and not those who could grant it, for those who are oppressed and not the oppressors. But what would it mean if the powerful actually heard the call of nonviolence as directed towards them? What would it mean if nations with billion dollar war budgets actually considered the moral mandate to move towards nonviolence as something for themselves? What would it look like if those who oppressed actually learned from Black people who were trying to teach that the best way to solve their problems actually was to work diligently to end situations of oppression and address the root causes of violence through nonviolence?

I know that we live in a violent world, and the impulse to return violence with violence is strong. But I am a Christian who was born in the midst of a war, a very violent situation like all wars. I also study violence; I teach about situations of violence, and I know firsthand the suffering caused by violence. That is exactly why I believe in nonviolence. I believe my government and our President, Joseph R. Biden, who ran a presidential campaign in part based on Dr. King’s nonviolent mission to to redeem the soul of America, should take seriously the call for nonviolence. I believe that a ceasefire in Gaza is the first step toward a nonviolent solution. I believe that working diplomatically can be a next step towards nonviolence. I believe that ending the occupation of Palestine is a crucial nonviolent move. And I believe working as hard as ever for a two-state solution in which Palestinians and Israelis can peacefully coexist free from apartheid is a significant nonviolent act. This current moment of calamity and catastrophe is also an opportunity to deepen our collective humanity. I believe in nonviolence and that nonviolence is needed today. I believe like the Bible and that old negro spiritual that we really should lay down the sword and shield down by this riverside and study war no more. I believe that nonviolence, as a strategy and a theology, is a legitimate path forward for peace, justice, and liberation today.

On behalf of the Alliance, I invite you to find your moral clarity in this moment, learn more about the way of nonviolence, and join us in being a witness to the power of nonviolence as an avenue for seeking God’s Beloved Community.

Reverend Elijah R. Zehyoue, Ph.D. serves as the Co-Director of the Alliance of Baptists. In this role, he is leading them through an effort to become an anti-racist organization. As a historian, theologian, pastor, preacher, and professor, Elijah is committed to using his many gifts to help people of all walks of life do the head, heart, and soul work required for our collective liberation. He is a graduate of Morehouse College (B.A.) and the University of Chicago (M.Div.) and Howard University where he earned his Ph.D. in African History. His dissertation focused on White Supremacy and its impact on the Origins of the Conflict in Liberia. Additionally, Elijah teaches African and African American Studies at the university level. Prior to coming to the Alliance, Elijah served on the pastoral staff at Calvary Baptist Church in Washington, D.C. Elijah is originally from Liberia, West Africa and grew up in Baton Rouge, La.

Header image by Tito Texidor III from Unsplash

Powerful and prophetic. This reflection calls us to look to the US Civil rights movement as a moral resource, a guide. It reminds us of the full message of Dr King, not just the dreamer, but also the prophet. We need to challenge empire and this is a case where the US empire is supporting the crucifixion of the Palestinian people. Thank you Elijah for this prophetic word.

Beautiful piece! It’s an awakening for non-violence!

Elijah, what you have written is surely one of the most important documents ever to be issued by the Alliance. It is a clear call for nonviolence and for a halt to the relentless murder of thousands of innocent civilians in Gaza. It recognizes that the United States with our limitless military resources is supporting Israel’s destruction of Gaza and that our government needs to be called to account for its participation in this indiscriminate slaughter of an entire people. Your statement places you in the forefront of the theological voices calling for an end of this terrible apocalypse engulfing innocent Palestinian people. Thank you for this clear and compelling statement.

Powerful and prophetic. We must keep pressuring our leaders for diplomacy and a ceasefire. The number of dead and lives destroyed by this conflict is a scandal. This Advent season is reliving the massacre of children of Jesus’ birth and hope can only be found in persistent calling the massacre and violence out as unjust and futile as a form of protest until our powerful leaders listen. Our collective lament and nonviolent protest is the hope of Advent that refuses to normalize or justify the vengeance. Thank you, Elijah. I look forward to the Alliance’s further nonviolent actions to bring peace, compassion and justice.

Elijah, Thank you.

Thank you for an eloquent reminder of the path of non-violence.

FYI, The US Peace Memorial Foundation recognizes those seeking alternatives to war. Through the US Peace Registry, annual US Peace Prize, and website, we seek to provide role models for antiwar actions-

USPEACEMEMORIAL.ORG