#BlackJusticeMatters

A Reflection on When I Became an Abolitionist

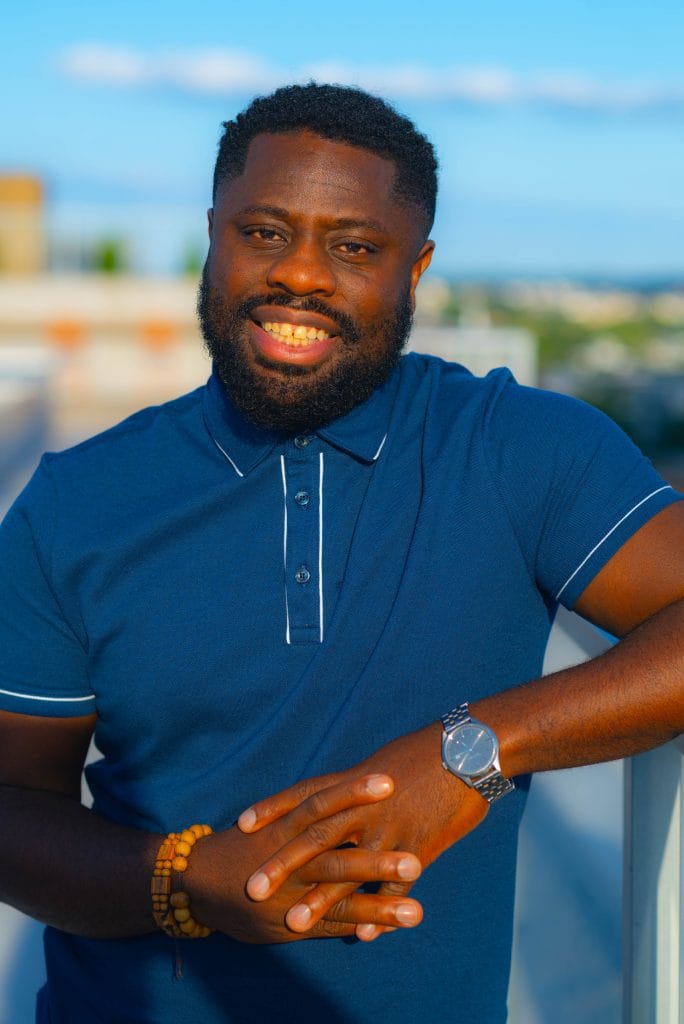

By Elijah Zehyoue

For Black History Month, I have been asked to share my thoughts on Black conceptions of justice. While I recognize that there has been great diversity of thought on how Black people have chosen to respond to the various unjust situations we have historically found ourselves in and still find ourselves in today, I have chosen to write about one particular conception of Black justice that inspires and convicts me–the Abolitionist Movement. The modern Abolitionist Movement is the continuation of the long struggle to abolish slavery and white supremacy and all their intertwined vestiges. Abolitionists today work towards the goal of eliminating imprisonment, policing, and surveillance and the reasons they exist by creating lasting alternatives to violent approaches to public safety, punishment, and imprisonment. I have chosen to write about this for two reasons. The first is that I believe this Abolitionist Movement offers a bold vision of a more just world that is highly compelling and consistent with the notions of freedom most seen within the Long Black Freedom Struggle. Secondly, like Vincent G. Harding, I believe that the conceptions of justice which have come out of the “river” of the Black Freedom Struggles–like this Abolitionist Movement–have and can lead to the great ocean of humanity’s best hope. It is my desire to introduce you all to a movement that I believe does this. This was a movement that took some convincing for me to become a part of, but I believe that what it seeks to do could transform our entire society. In the following paragraphs, I offer my reflections on how I got there and why I think it is so important. With our theme for the 2023 Annual Gathering, we are inviting members of the Alliance family to their own journeys of understanding the modern Abolitionist Movement. We invite you to read, study and reach your own conclusions about this movement and the issues it addresses.

I admit, I really wasn’t into the idea of Abolitionism when I first heard it. It was 2013. Angela Davis was in town because she had been invited to the University of Chicago to be our Martin Luther King, Jr. speaker. A few classmates of mine and some faculty friends told me that I just had to go hear her speak. Her ideas they said would change me, her intellectual heft would inspire me, her imagination would move me. I wasn’t quite sure. I had heard about her, and I was very skeptical. She thought we didn’t need police or prisons. And at the time, I just couldn’t get behind those ideas, especially because I was still considering myself as a moderate, someone looking for the middle ground between radical positions and the more reasonable ones. And this one seemed way too far. But at the urging of these people I trusted, I went just to hear her out.

Standing there with her quintessential afro, behind the pulpit of Rockefeller Chapel, she started with critique. “This space that we sit in,” she said, “here at the University of Chicago, is a space full of wealth and empire, built by a man who had too much money for his own good, was given too much power, and now this school is violent towards black and brown people, sweeping them from what should be their neighborhood.” She continued to speak and the more she spoke, the more annoyed I got. Who starts a speech at a host university with critique, why was she so mad? I could already feel the discomfort bubbling up inside of me. And yet she continued, “what I want to say to you students and those gathered in the community is this, we need to abolish institutions that are built on the exploitation of and violence towards black and brown, poor and oppressed people, we need to abolish institutions like the University of Chicago police, like the Chicago Police Department, like police departments in every municipality, we need to abolish prison, and abolish the death penalty, and abolish any system that terrorizes people.” The audience erupted in cheers and praise, and she could barely finish her words because all of that chapel was completely into what she was saying–except me.

After her speech, I told my professor friend, Forest, we can’t abolish the police, or prisons, we need them. They are necessary. We’ve always had them. So much time and effort was spent to build them, and even though they do bad things occasionally, they are still fundamental to our society. Y’all are crazy for trying to abolish them, who will keep up safe if you get your way? I was with you for some of it, but you have taken it too far. We need these things, you can’t possibly be serious about calling for their abolition, right? Forest responded, they haven’t always been with us, Elijah. We can pinpoint their origins and their direct ties to enslavement. They are human constructions, so we can dismantle them and construct new things that actually move us towards justice. And then he concluded, they really don’t keep us safe. No, no, no Forest. I left convinced that he and Dr. Angela Davis were wrong.

A few years later, I found myself standing toe to toe with heavily armed men in the Baton Rouge Metropolitan Police Department. It was early July and I had flown to my hometown to protest the killing of Alton Sterling, a 37-year-old man shot to death as he sold CDs outside a corner store. Being from Baton Rouge, I was devastated about what had gone down on the streets of my city, and so I wanted to do something. I flew in on a Saturday night, and that Sunday morning I spoke at a few churches—Black and white, and then Sunday afternoon, I went to protest peacefully. As we walked down the streets—streets I had known all my life—I could feel the police watching us. Scrutinizing our every move. Surveilling us as though we were the ones who had just killed an innocent person. None of it felt just. But all of it seemed normal. But then it got more intense. As the protest was ending a group was beginning to gather in a random field as they shouted #blacklivesmatter. My little sister and I joined them. As they were chanting, the police got on the loudspeaker and told everyone we had to disperse. A few seconds later an older black woman announced herself as the owner of the land and said that she wanted us to be there. “I invite them on my land,” she said. The police ignored her request. Again, they stated that everyone needed to disperse or they would move in with their battalions, tanks, and shields. They inched closer and closer to us, until they were standing right there waiting on the signal to forcibly remove us. And once they got it, that’s exactly what they did.

Later that night the Chief of Police and the head of the Louisiana state troopers were on the news. They recounted the events of that day on Government Street and said that protestors had antagonized the police—they were throwing stuff and left them no option but to respond the way that they did. I was livid, hurt, devastated. Up until that moment—and maybe I was extremely naïve—I didn’t believe that police officers or any public officials would lie. I believed that they took seriously their call to be protectors of the people. But they did lie that day. They lied on us, they lied about the situation, and they lied more to cover up the violence that they did to people protesting and to Alton Sterling.

A few weeks after that moment, I found myself in a conversation with a black policeman in New Orleans who had been invited to a church conference where I spoke. He spoke, too, and spoke all about how bad the situation with Alton Sterling really was. I felt kinship with him and I recounted my own experience in Baton Rouge. I expected him to feel my pain and share in my outrage. But he didn’t. He said the police acted appropriately that day. He said we should have gone home, we made our points. And did we really know the person we were protesting for? He continued protecting the order, saying that it was more important than allowing the people to protest for justice. And in that moment, I began to weep. I cried like I have never cried before. I was embarrassed about crying but I couldn’t help myself because my world fell apart. It was at that particular moment that I lost hope in the ability of the police to actually provide justice. Up until that point I believed that individual people could reform problematic institutions. But that moment, which could have been one of human solidarity, of honoring the life that was taken, of giving wise counsel to a young black man, of legitimizing our call for justice, was one where this officer chose his institution over human life, chose his brothers in blue over his siblings who were black, chose his commitments to the empire over his love of neighbor.

And so as I sat there crying, tears flowing uncontrollably from my eyes, the Spirit of God began to whisper to me through the voice of Angela Davis. It’s almost like her whole speech from earlier played verbatim in my head as I heard her make the argument to me that Alton Sterling’s death was not accidental but a consequence of the structures of policing and incarceration. I heard Bryan Stevenson’s voice talking about how the police treat you better if you are white and guilty, than poor and innocent. I heard Forest telling me that the police did not keep us safe but caused us more harm. And then I began to think about that harm. I thought about Trayvon Martin, and George Zimmerman endowing himself with police authority to subdue, capture, and kill young Trayvon. I began to think about Michael Brown, Jr., and how the police left his dead body in the streets of Ferguson, Mo., for four hours without calling for medical attention for him. I began to think about Sandra Bland and how she was pulled over for a traffic violation and never seen again. I began to think about Laquan McDonald shot down on the side of the streets by Chicago police, of Tamir Rice killed in the park by police, of Breonna Taylor shot in her bedroom by police. I began to think of Amad Diallo shot several dozen times by the New York City police and Eric Garner choked to death by that same force, of Oscar Grant shot to death by BART police, and later George Floyd suffocated by Minneapolis police. I began to think of all the harm that police caused us–the thousands of victims each year of police killings. The hundreds of thousands of victims of police profiling which left many emotionally harmed, physically incarcerated, or dead. And again, I heard Angela Davis’ voice just speaking to me saying, you cannot reform a fundamentally oppressive institution, a reincarnation of slavery, and so we must abolish all institutions that are built on the exploitation of and violence towards our people.

See my friends, that day everything changed for me. I saw with my own two eyes the violence inherent in police and lengths they were willing to go to protect themselves from any scrutiny and critique of their behavior. And I ultimately realized that Angela Davis and those other abolitionists were right. They knew what they were talking about, and I should have listened to them. Angela Davis knew that even with her PhD in philosophy and work as a professor, she could still be targeted by the criminal legal system as she was in the 1970s for her work with the Black Panther Party. California prosecutors sought the death penalty for her and tried to have her killed. She defended herself and won, but she knew that she was lucky. She knew too much about those systems of policing and imprisonment, mass incarceration, Christian supremacy and white supremacy and how they all worked together for evil. As she spoke that day she spoke from her wellspring of experience as a participant in and scholar of the Black Freedom Struggle. As she spoke, she knew too much about the historic plight and conditions of Black folk. She knew too much about how the criminal legal system ate Black folk, brown folk, Indigenous folk, and poor folk for lunch and so like Jesus she was adamant that the oppressive system had to go.

But it still took me a minute to see it, because I hadn’t read enough, or I hadn’t read enough of the right things, or because I hadn’t seen enough or because I hadn’t seen enough of the right things, or because I hadn’t trusted the voices of others enough who lived this each and every day, so I did not understand why the police had to go. I had not been paying close enough attention to the history of policing nor the history of the Black Freedom Struggle from Frederick Douglass to Freddie Gray who always named the role that policing played in our oppression. But I have since learned and now I see. I believe that the police need to be abolished. They cause more harm for Black folk than they do good. I believe prisons are obsolete, and they do not really keep us safe.Instead they are like Michelle Alexander informs us, an extension of the racial caste system that started during enslavement. I believe that ICE should be abolished. It’s a modern construction that uses taxpayer money to terrorize vulnerable immigrant communities. I believe that the systems of laws, policies, and social norms that support mass incarceration and criminalization of Black and brown people needs to be dismantled. I believe that white supremacy, in all its many manifestations, needs to be undone. I believe that we need to reimagine what public safety is, what constitutes criminality, and what justice looks like in this country and around the world. I believe we need to turn to the abolitionist movement—a movement that comes out of the wisdom of Black people, which has its origins in the fight against the institution of slavery, Jim Crow, and the system of expanded policing and mass incarceration and look to new visions of freedom. I believe we need more people who believe in justice. Real justice, justice that abolishes oppression, justice that repairs harms, justice that reimagines what freedom and liberation can look like, and justice that transforms our lives and our world.

Elijah Zehyoue is co-director of the Alliance of Baptists. He is a graduate of Morehouse College (B.A.) and the University of Chicago (M.Div.) and served as associate pastor at Alliance congregational partner Calvary Baptist Church in Washington, D.C. from 2014-2021. He is a pastor, preacher, scholar, and teacher. He is in the dissertation writing phase of a Ph.D. in African History at Howard University where he studies the Trans Atlantic Slave Trade and the Origins of the Liberian Civil War. Himself an immigrant from Liberia, Elijah’s family came to the U.S. to escape that country’s civil war.

TO my Morehouse brother, Rev. Elijah, Thank you for sharing your transformation story. It is such an excellent example of how the power of witness can become the catalyst for a witness to power!

Many thanks Elijah for your provocative, personal and challenging articulation of the movement that is calling us. Blessings to you as you shine the light of justice and hope.