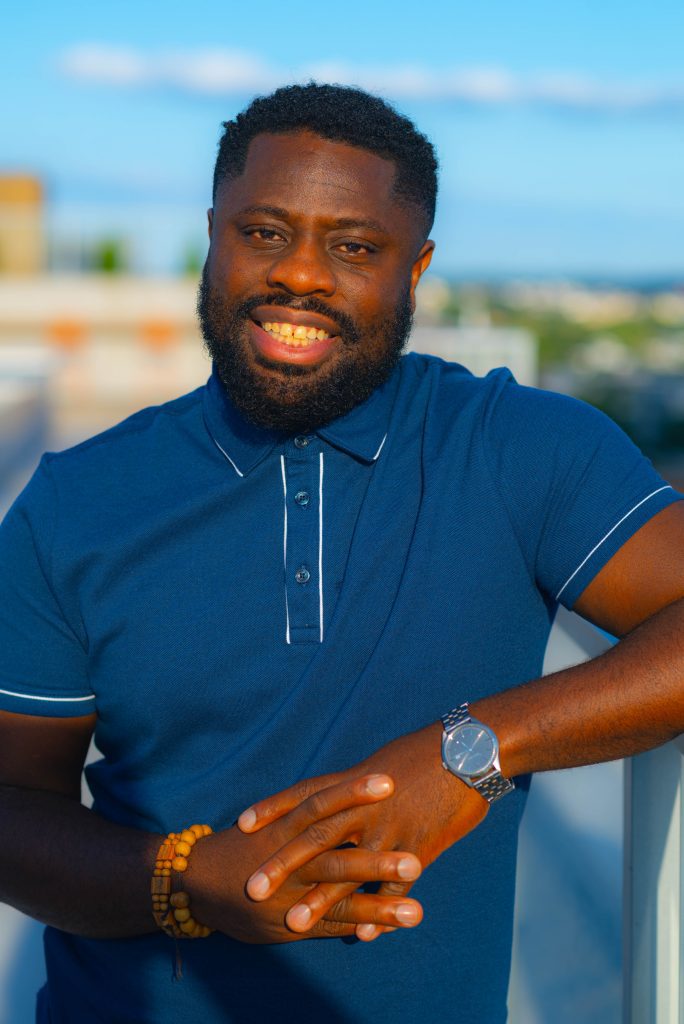

by Elijah Zehyoue

On the third day of what had already been a powerful trip to Olinda, Brazil, to celebrate the 20th anniversary of the Alianca Batista do Brazil, Pastor Paulo, one of the co-founders, invited me to come along with him and his daughter Maria Clara for a ride. He wanted to show me a bit more of the ministry of the church he and his wife founded, Primeira Igreja Batista Bultrins. As we drove through the neighborhood, I was excited to see it through his eyes. I was still deeply moved by the powerful gathering a few days earlier where I listened to inspiring sermons and workshops on reproductive justice, women rights, and Palestinian solidarity under the leadership of President Pastora Camilla. I couldn’t wait for what was in store next. The first place Pastor Paulo took me to was a house that served as the meeting place for the symphony orchestra that was connected to the church. To get there we had a bumpy ride on a steep hill in a poor community in Olinda. When we got there, we were greeted with tea and watermelon. He then showed me the musical instruments—the violins, violas, cellos, and bass. I was struck with the memory of my childhood. Briefly, I played the violin along with my brother, although he was much better and played for much longer. But more so than seeing the instruments was listening to Pastor Paulo’s logic for starting the orchestra. He said we have so many talented kids in the neighborhood and by developing their skills, we aren’t only teaching them how to be musicians we are giving them a chance to save their lives. He continued, “the future is bleak for a lot of these kids, too many of our kids, especially Black kids from neighborhoods like this are lost to violence, prison, and death, and the orchestra helps them to escape that future.” His words hit me heavy, this story was very familiar to me as Black person in the US, but before I could fully process all of that he said let’s go, there’s another place I want to take you. I want you to meet some of my church members. So, we drove down the hill and into another community.

As soon as we got there, the community members greeted Pastor Paulo, Maria Clara, Pastora Vena, and myself. They said welcome into the community. As I entered, I thought about the kids from the orchestra, some of whom lived in this community. I also thought about my cousins in Liberia and how this community did not look too different from theirs. This community, was one of the many favelas in Brazil. And as we walked throughout, it looked like what I expected a favela to look like. Humble houses, narrow streets, and stray dogs and cats. But what I wasn’t expecting was just how intimately Pastor Paulo knew the people in community and just how warm it would feel. Even though I’m a liberationist thinker and a progressive pastor, I had still been taught that favelas, like other hoods, were places to be scared of and that the people were to be feared. But I was shocked as Pastor Paulo walked from house to house knocking on doors, giving hugs to old ladies, holding babies, playing with dogs, and even providing counseling and parental love to the young men and women we encountered. People who I would have thought could have posed a threat to us were his friends. They were asking him when would he come to eat with them, would he pray for their children, could he come and check on their mom. They were teasing him for his soccer team losing. It was a surreal experience partly because so many people were Black, and it gave new language to anti-racist ministry, expanding it beyond the U.S. and across the globe. This experience opened my eyes to new ways of seeing and challenged me beyond measure. In that moment I began to feel guilty because I thought my own ministry has been too sanitized and too distant from the actual suffering in the world. I wanted to follow Pastor Paulo each day because of the work the church was doing in the community. With each person, there was a story, and with each story there was more profoundity, layers and depth to the human story. I remember while we were entering a woman’s house, I asked Maria Clara if she was a church member. She said no. Most of them are not members of the church, but it doesn’t matter, the church is in the community and so they know us. I could see why Latin American liberation theology was birthed from communities like these, filled with people who actually need a spiritual tradition that could transform their lives.

I had so many questions for them both after this, but before I could ask we kept moving. We kept meeting more people and ministering to them. Talking to them, visiting with them, and just being with them. It was a ministry of presence if I had ever seen one. At one house for example I was chatting with a mother of three, while Pastor Paulo was chatting with her son. She shared with me that her mother had been born in the community, and she had lived in the community since she was a child, and now her children and her grandchildren were also living there. I asked her what it was like before. She shared that it’s changed some but not that much. There was one big change, however. The community, she said, used to be named after a violent figure. And the community members didn’t like that. They thought it wasn’t a reflection of who they really were or who they wanted to be. So more than 20 years ago, they arranged a community meeting, took a vote, and changed the name to Vila Esperança or village of hope. They wanted their community to be a symbol of hope. They wanted their children to be proud of where they come from, and despite what they had been through and what they might go through, they wanted their community name to represent the vision they have for themselves and what they know God has for them—Vila Esperança.

When I think about the Alliance of Baptists and the state of affairs of the U.S. and the world, I think we badly need the moral vision of my friend from the Vila Esperança. In fact, we badly need to learn from Vila Esperança itself. See, despite my best intentions and all of my hard work to be an anti-colonial, anti-racist, anti-imperial person, some of that stuff is still inside me. It’s still inside of many of us. And perhaps the only way it will go away is if we enter into deeper relationships with people from the places we may be afraid of or have forgotten or where our institutions have done the most violence and engage with them on new visions of what is possible. Being in the Vila Esperança with our partners from the Alliance of Baptists of Brazil, specifically, and really anytime I have been with our international partners whether meeting Phillip in Kampala or having church with Coralia in Cuba, I have realized that we have so much to learn from them! For they have experienced so much of what we are struggling with, and they have developed the tools to confront it.

The Alliance is on a journey to become an anti-racist organization. Becoming this is more than just changing our beliefs, it’s about changing our actions, what we do and who are we are with, where we are and how we spend our time and resources. And many of our partners are already doing that. They can show us how to be anti-racist and be the best version of ourselves in these trying times. Our partners in Brazil have already lived through a dictatorship and figured out how to have courageous and prophetic ministries through it all. Our partners in Cuba manage to share and minister with a spirit of abundance despite a decades-long US blockade of most goods to their country; our partners in Mexico are teaching at the intersection of liberation theology and indigenous religion, despite the persistent attacks on their people and their beliefs. Our partners in Zimbabwe are countering the pernicious teachings of the SBC and other imperial missionaries by teaching about the love of God from the African perspective; our partners in Uganda are showing the love of God in alternative and transformative ways to marginalized people especially those who have HIV and those who are queer and in the LGBTQ community. Our partners in Georgia and Palestine are literally being the light in the darkness, peacemakers in active war zones. All around us the Alliance is connected to a global village of hope. Yet our connection to this village shouldn’t make us arrogant or full of ourselves. It should humble us and challenge us to ask ourselves have we really got this thing figured out? It should push us to ask the question of what do we have to learn from our friends? It should make us want to scrap some of what we hold dear and embrace the living waters they have to offer to us.

Look, it’s tough for so many of us to truly embrace the wisdom that comes from people we believe we are better than. Capitalism teaches us that money equals value. And because we Americans by definition and hegemonic structures have more money, especially those who are white, many of us think that we are better than the rest of the world and that we have things to teach them, but not that they have things to teach us. This couldn’t be farther from the truth. In fact, we have much more to learn than teach. My hope and prayer is that those of us Americans in the Alliance reject that. For we have so much to learn about what it means to be church, what it means to be courageous, what it means to be communal, what it means to be anti-racist, what it means to be open and affirming, what it means to be in solidarity, what it means to believe that God really will provide, make a way, and never neglect us simply by learning from our global village of hope. Like us, our partners in the world do need money to support their ministries, and we must give generously to support their powerful ministries, and I invite you to do so. We need their wisdom, we need their love, we have their friendship. And together we can keep building this Villa Esperanza around the world, now and forevermore.

I invite you to give generously to the Alliance of Baptists to support our ministry partners. Today there are two specific requests in Brazil. One for the orchestra and the other to put a roof over the home of a woman in need.

Reverend Elijah R. Zehyoue, Ph.D. serves as the Co-Director of the Alliance of Baptists. In this role, he is leading them through an effort to become an anti-racist organization. As a historian, theologian, pastor, preacher, and professor, Elijah is committed to using his many gifts to help people of all walks of life do the head, heart, and soul work required for our collective liberation. He is a graduate of Morehouse College (B.A.) and the University of Chicago (M.Div.) and Howard University where he earned his Ph.D. in African History. His dissertation focused on White Supremacy and its impact on the Origins of the Conflict in Liberia. Additionally, Elijah teaches African and African American Studies at the university level. Prior to coming to the Alliance, Elijah served on the pastoral staff at Calvary Baptist Church in Washington, D.C. Elijah is originally from Liberia, West Africa and grew up in Baton Rouge, La.

Recent Comments